Redefining the epic: women writers’ interventionist novels

Ever wondered how stories affect us? They tend to govern our actions, values and many times, influence our way of thinking. The world is full of stories. It is said that humans require stories more than bread, in order to survive. The art of storytelling isn’t a skill that came to existence a decade or a century ago. Storytelling has been prevalent since the advent of humankind. From cave paintings to the rise of novels, stories have survived the test of time. Within the art of storytelling, a form that has recorded our cultures and has altered our way of living is an epic. Technically speaking, an epic is a long poem, generally derived from ancient oral tradition, that narrates the adventures of heroic or legendary figures or the historical significance of a nation. Be it Homer’s war-filled Iliad or Valmiki’s Ramayana that sets the path to righteousness, the epic has survived eons and continues to be sung in almost every household in one form or the other.

Epics glorify war and its heroes. They uphold righteousness and sing of mighty kings and their victories against the evil forces. Often, Gods intervene and side with the kings of their choice. Majorly, the epic remains about men – kings, male warriors, on foot male soldiers and decision-makers. What if the epics were about women or at least, about women too? What if women weren’t mere pawns to get married to and reproduce heirs? What if Homer’s Penelope wasn’t given the status of an ideal wife or if Valmiki’s Sita wasn’t shown only as a damsel in distress? To answer all these, women writers have decided to pick up the mighty pens and give a voice to female characters. They share their perspectives in the age-old epics that are written in modern times. They’re telling their own tales because nobody else has, even after so many decades.

These interventionist novels by women writers make ample space for a female character’s childhood, her character development and how their heroism becomes a whole new, never spoken brand of heroism. These novels become necessary reads as Madeline Miller said, “Epic has been traditionally male”. Read more about some of the works that highlight women characters and their journeys.

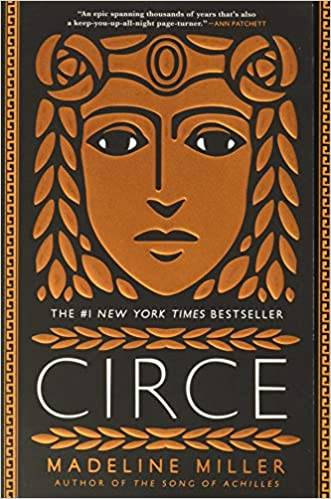

Circe by Madeline Miller

In her book, Circe, Miller talks about a character with the same name in Homer’s epic ‘Odyssey’, which accounts for the return of the king of Ithaca after the Trojan war. Circe’s character appears as a powerful witch in Homer’s epic, who turns soldiers into pigs. Not much is said by Homer about Circe. Miller not only gives voice to her character using Homer’s account but also tells the readers about Circe’s own life, her anxieties and loneliness, and how turning soldiers into pigs was an act of defence as she was stranded alone for years on an island. She turns Circe into a worthy character who is knowledgeable and worthy. Miller calls Circe, “an embodiment of male anxiety about female power”. She is a celebration of indomitable female strength in a man’s world.

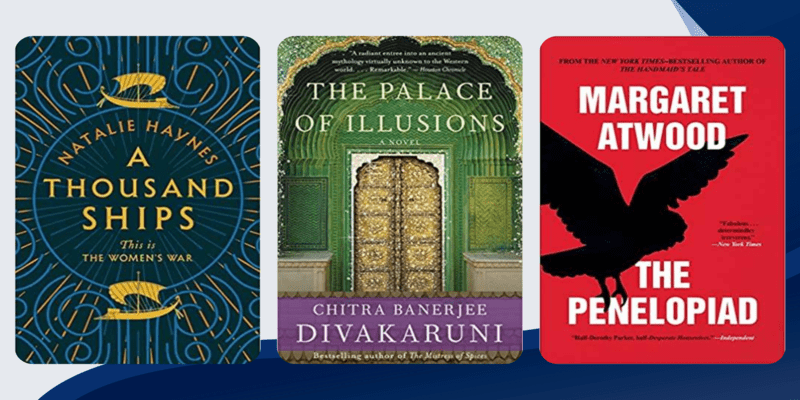

A Thousand Ships by Natalie Haynes

Homer’s Iliad is an account of the tenth year of a decade-long war between the Greeks and the Trojans. It details Helen’s (Greek queen) escape with Paris (prince of Troy) and the aftermath that followed. Haynes’ ‘A Thousand Ships’ talks about the warriors in the war. The difference between her warriors and that of Homer’s is that Haynes’ warriors don’t bathe in blood. They do not abduct women or children or slaughter slaves. Her warriors wait. They manage the household… affairs of the land called ‘home’ and keep it going while men kill each other. She makes it a point of notice for the readers that while Epics only count acts on the war front as courageous, waiting for someone’s return at the time of war is equally courageous. She presents her female characters as equally or rather, more heroic, for their heroism does not fall under raping or enslaving people.

The Penelopiad by Margaret Atwood

Homer’s Iliad will be referred to once again. Rhyming with the former poet’s title, Atwood’s The Penelopiad is a novella that brings out the character of Penelope, the wife of the king of Ithaca. Penelope spends 10 long years in wait for her husband. All this while, rejecting suitors who approach her only to pry upon her territory. She is regarded as the ideal wife by Homer, while her role as a queen who manages her homeland without any help has not been mentioned. Atwood talks about Homer’s standards while describing fidelity in a relationship. She notes that the term had a different interpretation for men and women as it was acceptable for Odyssey to mate with Circe on his way back home, but Penelope’s purity was in rejecting suitors. Atwood also targets Penelope for allowing the rape and murder of her maids by Odyssey.

The Palace of Illusions by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni

Vyasa’s Mahabharata is a well-known Hindu epic and so is the character of Draupadi, who was subjected to harassment and injustice. Yet, somehow, the Epic remains about the five righteous kings. Divakaruni shares Draupadi’s viewpoint in a patriarchal world. In most epics, women characters are only introduced at the time of getting married. However, Divakaruni talks about Draupadi’s childhood and her formative days. In the novel, Draupadi is not just a pawn but a fiery queen who wants justice for her wrongdoings. With a shift in the narrative, the kings and their thirst for power are sidelined. Draupadi’s perspective forms the crux as readers get to know about her worries, mistakes and learnings. The first-person account is worth spending several days on.

Sita’s Ramayana by Samhita Arni and Moyna Chitrakar

This graphic novel, which is a collaborative effort of writer Samhita Arni and illustrator Moyna Chitrakar, gives Valmiki’s epic a different edge. The narrative of Sita comes to life in this novel. What makes the novel distinct from the ones talked about above, is its retention of the tradition while adhering to the modern. Chitrakar chooses the ‘Patua’ tradition of storytelling through panels shared with the audience. This form of art makes it possible for palaces, jungles and hills to come alive using only a few strokes with primary colours. The highlight of the novel is the point from where Sita’s plight begins – her banishment over doubts related to her purity. While for most of the audience Ramayana’s conventional narrative is over after Sita and Ram return to Ayodhya, Sita’s story does not end there. In fact, it is the new beginning of her story. This Sita is far from being a ‘damsel in distress’.