Hong Kong’s ‘magna opera’

Hong Kong ranks 168th in terms of area coverage of cities around the world. In terms of population, it consists of 7.5 million people. How is it then that a city with a comparatively small area and population density has ended up creating countless classic movies? Once called the ‘Hollywood of East’, Hong Kong cinema has managed to deliver cinematic masterpieces since its dawn. Hong Kong’s cinema is the binding thread in the history of the Chinese language and Chinese cinema. Out of numerous national cinemas, Hong Kong’s was once the most distinctive of them all. It led to the rise of many peculiar genres, notably Kung fu and Wuxia.

It was once also the largest exporter of films despite its small city size. Due to an inclusive population and worldwide diaspora, Hong Kong cinema made ample space for acceptance and diversity along with heritage. Local stars such as Jackie Chan and John Woo became Hollywood celebrities, and the likes of Chow Yun-fat and Jet Li also had the chance to showcase their skills in front of a global audience.

According to film historian David Bordwell, at its peak, Hong Kong produced “arguably the world’s most energetic, imaginative popular cinema”. Hong Kong cinema was once the third-largest motion picture industry in the world. And now, decades after, Hong Kong has managed to retain its distinctive nature and quality to absorb diverse cultures on screen. The cinema also contributes more than five percent to the country’s economy. With such a rich cultural heritage, let’s look at some of the productions that contribute to the complex exploration of the human condition.

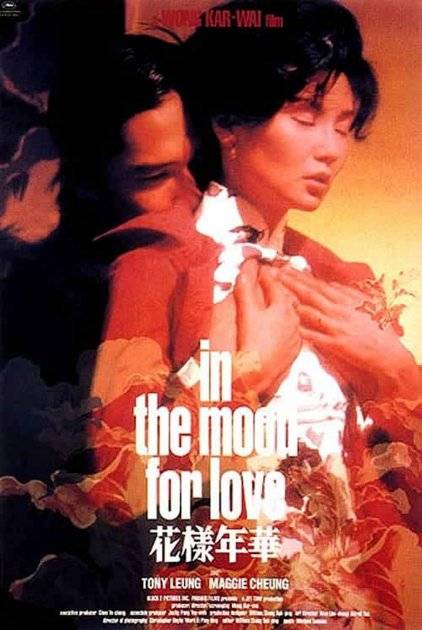

In the Mood for Love (Director: Wong Kar-wai)

Based on writer Liu Yi-Chang’s stream-of-consciousness novella, Intersection, In the Mood for Love revolves around the protagonists — two would-be lovers — who cross paths before parting for a long time. In the Mood for Love is, to its core, romantic, unlike the famous Hong Kong cinema focusing on martial arts or recurring action. In their search for fidelity, the protagonists, Mr. Chow and Ms. Chan, discover the love affairs of their respective spouses. They attempt a role-play wherein they play out hypothetical breakups with their partners. A while into the plot, in order to act out the infidelity of their partners, they consummate their longing for each other, though they know that it cannot last. Wai’s masterpiece is a tale of hopeless glances and unrequited love.

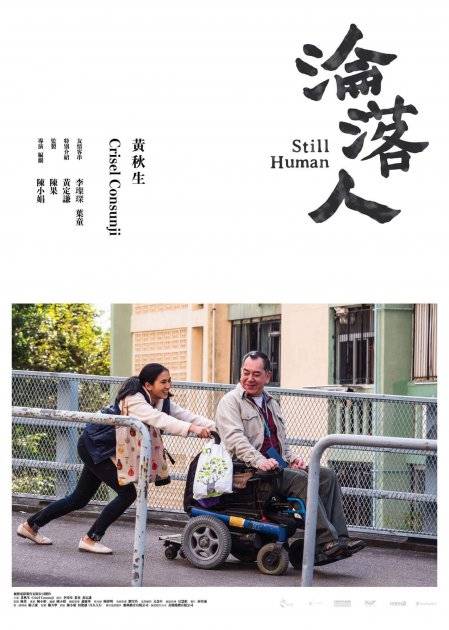

Still Human (Director: Oliver Chan Siu-kuen)

A Filipino domestic worker carries a disabled man in this extremely heartwarming film by Chan. The simplistic masterpiece revolves around two lost individuals who, in the midst of losing their hope to live, find the will to keep going. Their paths cross and entwine in such a manner that they end up becoming a part of each other’s unfulfilled dreams. Still Human was nominated for the 38th Hong Kong Film Awards in eight categories and managed to bag three, including veteran actor Anthony Wong Chau-sang’s Best Actor for his portrayal of the disabled man.

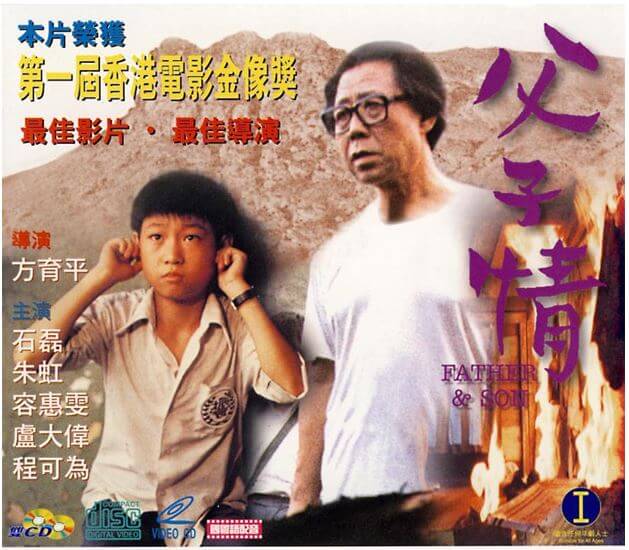

Father and Son (Director: Allen Fong)

The complexities of father-son relationships are known around the world. Exclusively in South Asian families, where familial ties are kept strong, it becomes important that such tangled relationships are solved. Fong was named ‘Best Director’ in the Hong Kong Film Awards for his movie Father and Son. This film has a tinge of Fong’s autobiography and serves as discoverer for the sub-genre of Cantonese father. The plot revolves around a disciplinarian father and his school-hating but cinema-loving son. The father is not so well-off and wishes for his son to grow up and do something great in life. Even if this film was based in a certain context, it touched hearts around the world. Though it had a working-class flavour, it did not fail to impress audiences from varying social backgrounds. The film also won the Best Film Award at the Hong Kong Film Awards.

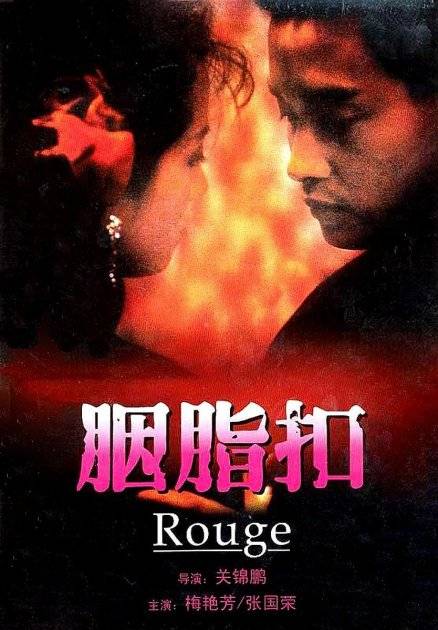

Rouge (Director: Stanley Kwan)

Released in 1988, Stanley’s Rouge is an adaptation of a novel under the same name by Lilian Lee. This contemporary ghost story has been canonised as one of the greatest Chinese language films of all time. The highlight of the film is Anita Mui’s performance as a ghost of a courtesan who comes disguised as her lover after he has survived their suicide pact in 1934. Kwan’s chilling, nostalgic, supernatural drama revolves around the transient city life and also reminds of the multiplicity of love in a well populated city. The courtesan mourns the realisation of how we don’t kill ourselves for love anymore like we used to. The film bagged six awards between 1988 and 1989.

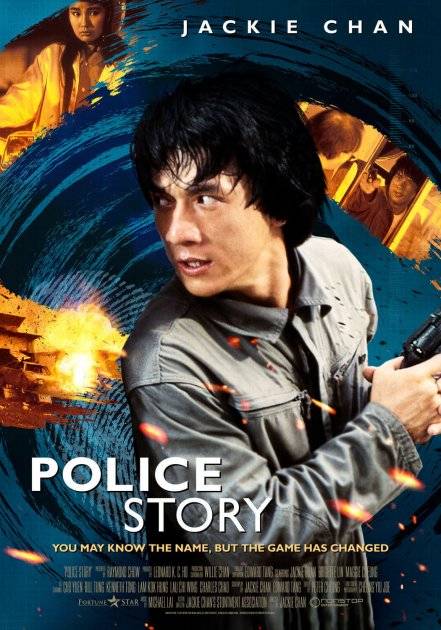

Police Story (Director: Jackie Chan)

Hong Kong’s most famous director and actor, Jackie Chan, provides the audience with a share of athletic choreography in this film. Full of action, plot twists, and suspense, Police Story is a modern classic. The film has a glass-shattering climax and breathtaking stunts, including the actor hanging from a speeding double-decker bus with the help of only an umbrella. This blood-rushing, action-filled flick was able to collect over US$ 264 million as a series. The 1985-parent film is survived by four of its follow-ups which have received equal fame and critical appreciation.

Hong Kong cinema has time and again proven its worth to the world. With the films, we just talked about and countless more, directors kept experimenting with genres, cultures, and, most importantly, complex human emotions in their Magna Opera.